Before designing a programme, it is crucial to understand the context in which it is operating to ensure that everyone involved has a similar understanding of the situation and that the programme is designed to address the relevant issues with the right people. Context analyses are often outsourced to external consultants. However, our experience shows that some of the knowledge, understanding and connections that the external consultant acquires during the analysis may be lost in the transfer of information. Therefore, we suggest having the context analysis done in a participative way with skilful insiders; having the wisdom in the room by inviting the right people. This way, the exercise can result in a deeper understanding and higher usefulness to the design of the programme. The context analysis usually consists of two interlinked exercises:

- Mapping and analysing stakeholders

- Mapping and analysing factors

Map and analyse the stakeholders

The participatory stakeholder analysis helps you to identify and map all relevant actors and their roles, responsibilities, relationships, interests, and relative influence/power. Relevant refers to the actors who have something to do with the impact the programme aims to contribute to. It is important to make sure all actors are taken into account, including vulnerable and underprivileged groups who may otherwise be overlooked. This exercise is of most value when performed in a group or workshop setting, and will help identify which strategic stakeholders need to be involved in your programme, and in what way. During the programme, power relations may change and new stakeholders may appear or knowledge gaps regarding existing stakeholders may be filled. It is therefore advisable to review your stakeholder analysis on a regular basis.

There are three types of stakeholders for you to consider:

- Communities: The people who experience the problem directly, and interact with problem solvers.

- Problem solvers: The civil servants, non governmental organisation (NGO) staff, frontline responders, and others on the ground.

- Policy and decision makers: The people who have access to resources and control allocation, or can influence decision making.

It is important to include informal stakeholders in the analysis and not only the formal ones. Formal stakeholders are institutions or people with legal status, such an government entities, private corporations or NGOs. An informal stakeholder is a person or group of people without legal status, but with a vested interest in the impact the programme aims to contribute to. For example, a formal stakeholder could be a member of the ministry of health, and an informal stakeholder could be a local activist campaigning for health rights. Informal stakeholders can be very influential but are easily overlooked.

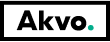

Create a stakeholder map

In a stakeholder map, all actors that are relevant for the programme’s success are noted down on colour-coded cards (different colours for government, civil society, private sector, knowledge institutes), and organised according to the level at which they are most active (international, national, regional, district, community). Links between actors can be indicated with different types of lines.

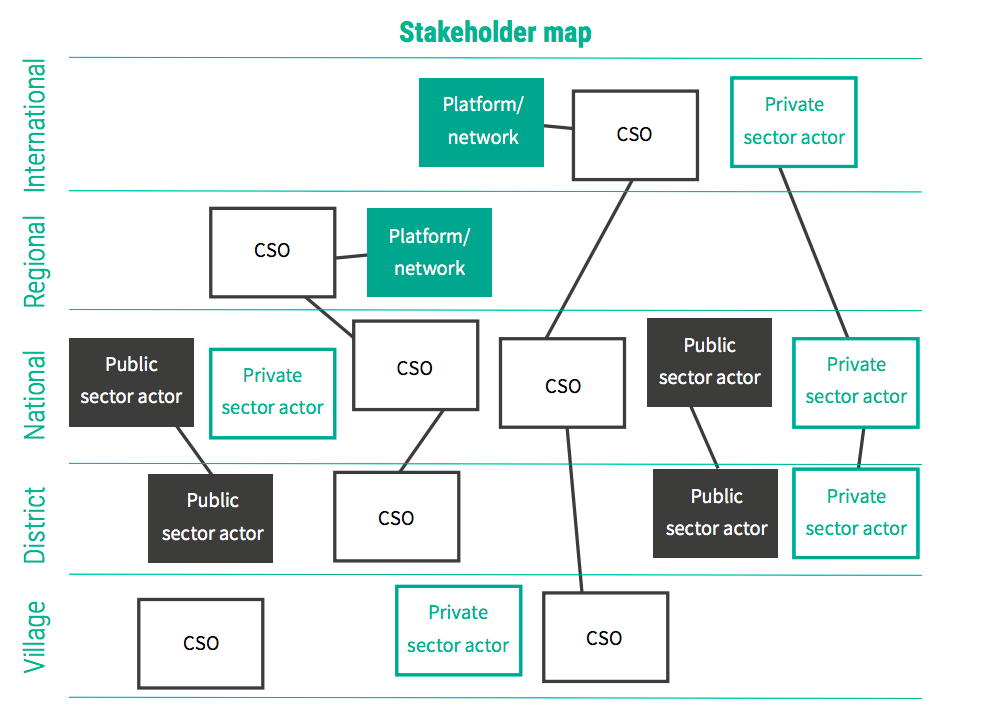

Create an influence-interest matrix

Once all stakeholders have been made explicit, you can create an influence-interest matrix to discover more about each actor’s interest in and influence on the data collection and data-based decision making in the programme. The following questions can be useful in this discovery:

- What is their influence on the problem?

- How might this person benefit from the programme?

- What could this person do with better data on the problem?

- How does data support this person’s decision making now?

- What could they do to undermine the programme?

- What is the best way to keep them engaged?

- How can they contribute to a solution?

All of the actor cards can be plotted on four quadrants of the y-axis (interest) and x-axis (influence), according to how interested they are in the success of the specific programme, and how much influence they have in making it happen. Powerful stakeholders can also have a strong negative effect on the success of the programme. During this exercise, it is possible that actors who had not yet been identified in the stakeholder map are included.

While doing both exercises, keep in mind that there are both formal and informal power structures to take into account. Government would be a formal power structure, while activist groups would be an informal power structure.

These exercises produce the richest insights when done in a participatory way in order to include different perspectives. The discussions generated by the exercises help to bring out the different perspectives at a time when these can be taken on board and to create co-ownership and a shared focus for all involved.

Map and analyse the factors

Besides stakeholders, external factors also need to be taken into account when designing a programme. Are there any environmental, historic, political, cultural or socio-economic factors that are likely to have an effect on the success of the programme, and in turn, on that which the programme can have an effect? Identifying these factors will help to determine the problems and opportunities that need to be addressed. Documenting all factors at play will help to justify decisions on the programme’s scope and focus. Besides data research (chapter seven), brainstorming and interviewing key stakeholders is helpful in identifying and documenting factors. This can be done by creating a problem tree.

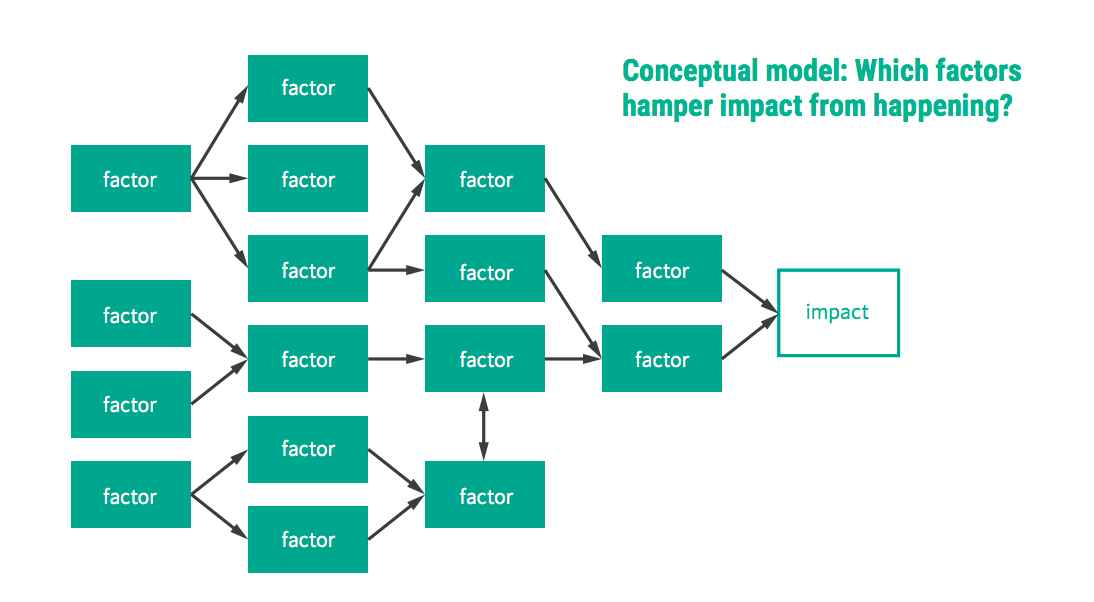

Create a problem tree

A helpful method for mapping out factors is creating a problem tree or a conceptual model. Start by defining the impact that the programme aims to address, such as sustainable and inclusive water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services. Write it on a card and stick it to the wall. Using the knowledge of the people in the room, brainstorm the various factors related to the desired impact: what is hampering the achievement of this impact? Why is it not happening now? The next step is to cluster the cards according to topics, and then organise them in cause and effect relationships on a map. In our experience, no more than 25 factors works best to avoid spreading the focus too thin. Such a map, or conceptual model, helps to create a common understanding of the problems, how they are interrelated, and what the root causes are. It can also help to distill what activities should be put into play to address the problems outlined by the programme, and what the scope of the programme should be.

By doing these exercises in a participatory manner, the relevant stakeholders should reach a common understanding of the problem that the programme is trying to address. What are the issues that lead to the overall problem and how are they interrelated? Once you’ve conducted your context analysis, you can use all of your knowledge and information to design a Theory of Change.

Do you want to learn more? Download our eBook!