Over the last six years, Akvo’s PMEL team has designed and facilitated 23 participatory Theory of Change processes for organisations and programmes in the international development and not-for-profit sectors. The majority of these processes also included support in developing monitoring frameworks.

During this time, we realised that our approach to programme design is unique. It is practical, concrete, and participatory, and it leads to actionable Theories of Change (or change logics, or impact strategies, as you prefer) and monitoring which is useful for learning and steering, not just reporting. Knowledge may be power, but it’s far more powerful when shared! So in this blog, you'll find our lessons learned and insights from the past six years.

1. Think systems

ToC is a systems thinking approach. Bob Williams explains systems thinking along three main lines:

-

An understanding of interrelationships: everything is connected.

-

A commitment to engage with multiple perspectives: people see things differently.

-

An awareness of boundaries: what is in and what is out, who has the power to decide that, and what are the consequences.

Zooming out is required to see the bigger picture, the context and how things connect. But as we cannot address everything, we need to zoom into the scope of our area, where we can see more detail. We live in a globalised world, where problems and opportunities are connected across boundaries, and complex issues require more than a single standard project by one organisation. Theories of Change are useful for designing interventions aimed at contributing to systemic change for a number of reasons:

-

They are based on a collectively constructed understanding of the context - the bigger picture.

-

They are developed in a participatory manner respecting different perspectives on how change happens.

-

They help to define the scope of an intervention together with stakeholders.

-

They are meant to be reflected upon regularly and used to guide decision making, thus enabling flexible adaptive programme management.

An awareness of systems thinking helps to appreciate ToCs and use them well.

2. No M&E without Design and Learning

It is not uncommon for programmes to have a monitoring system with a long list of (quantitative) indicators for which they collect a lot of data. With the indicator scores they produce graphs, and this is used for reporting: accountability to the donor. So far, so good, right? No. Indicators should not be monitored, intended results or changes should be monitored, and indeed, quantitative indicators can help with that. If a monitoring system does not show which intended results are being monitored (with indicators), but goes straight into listing and defining the indicators, what is monitored is the state of the individual indicators. Nothing less but also nothing more. This is easy to spot: the first or second column of a monitoring framework shows the indicators, and they are not connected to any intended results. Perhaps this is because the intended results are tucked away elsewhere, or perhaps there is no clarity on what the organisation or programme is trying to achieve. Either way, the organisation or programme is missing out.

Let’s zoom out of monitoring and look at what comes before it. This is the phase of programme design - thinking and deciding about what needs to be achieved (such as in a Theory of Change), followed by what needs to be monitored, why, and how (the monitoring framework). M&E officers are called that because they are not involved in the Planning or Design that precedes it. What needs to be monitored is a selection of intended results, outcomes mainly, perhaps some impact, and more straightforwardly: outputs. When a selection of intended results is monitored, and these are connected to each other in logical cause-effect relationships in a ToC, then the monitoring findings can be used not only to report, but also to learn about what works, what does not, and why. That is zooming out to what comes after monitoring: Learning and acting. From our experience, we’ve seen that when monitoring is done for learning and steering, it is also more useful for meaningful reporting. So our advice here is: monitor intended results (with indicators if you like), for your own use primarily. Using these findings can help you become more effective.

Designing a programme’s change logic and monitoring framework well is also the best base for an actionable online dashboard reflecting progress on selected intended results. Such portals or platforms are intended to support decision-making, and that works much better when the users know beforehand exactly what they need to see to be able to do their work better.

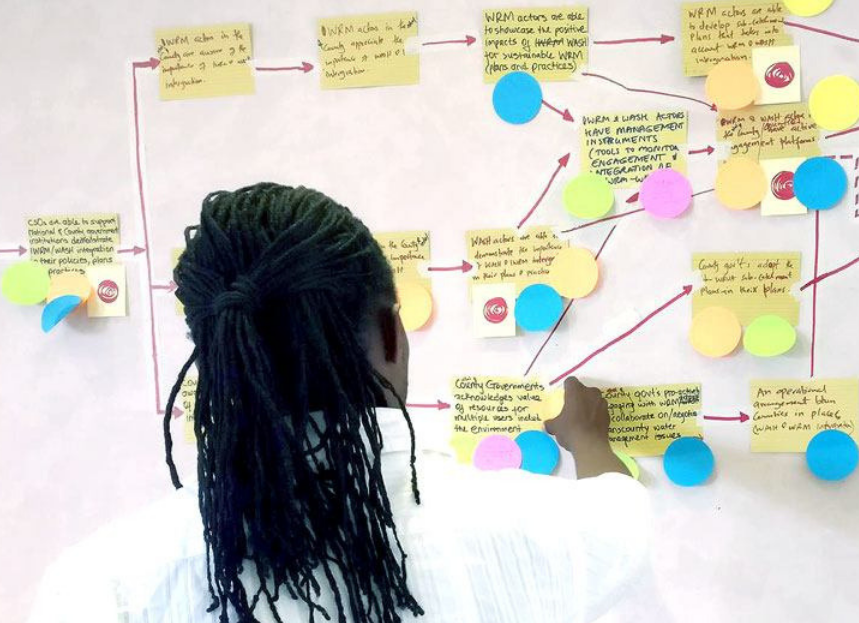

3. Do it together

Developing a useful ToC, which is not theoretical and abstract, is very much about getting the process right. Some programmes have a ToC as part of a proposal, made behind a desk by people detached from the reality of the field. When the programme is won, and the ToC has served its purpose, it risks ending up in a virtual drawer and not being referred to again. Instead, it should be used as a starting point for the inception phase, in which the programme partners improve the ToC together and use it as the basis for planning and monitoring. Developing a useful ToC requires a participatory process, where different stakeholders share their perspectives and collectively construct clarity on what they want to achieve. Such a process ensures higher relevance and quality of the content of the ToC, which also results in alignment of the stakeholders and a co-ownership of the ToC. This is especially important for consortiums, alliances, and multi-stakeholder platforms, where getting on the same page is essential.

I’ve mentioned the importance of a ToC as a basis for useful monitoring. But a ToC is also an excellent basis for activity planning. When it is clear what an organisation aims to achieve - the intended outcomes - the team can discuss what needs to be done to make those changes happen. This might be even more relevant in a (new) consortium, where organisations will be working together, and it needs to be clear which partner is doing what. So another piece of concrete advice: first agree on what needs to be achieved together, then decide on activities - and not the other way around.

In the case of a programme which is to be implemented in several countries, we’ve experienced that it is good practice to develop an overall programme-level ToC for the general focus, scope and approach, followed by context-specific, locally owned ToCs at country or project level - “nested” ToCs. The country-level ToCs are much more useful for the collective generation of a shared understanding, action plan, and monitoring, because at the local level it is possible to be more specific and concrete. The more concrete the intended changes and causal assumptions in a ToC are, the easier it becomes to decide what needs to be done to make it happen, what needs to be monitored, why, and how.

4. Zoom into the missing middle

We have come across organisations and programmes where problems have been identified, and strategies have been designed. Activities have been worked out, expected outputs have been described and output targets have been set. But there is little clarity on which effects the outputs are expected to have at the level of local actors, and how these changes are expected to contribute to the impact. That intended impact might be a far-away abstract idea about a better world, or be quite clear, sometimes even with targets. But in current international development cooperation, where most organisations work with local actors on (mutual) capacity development and behavioural change, impact does not happen by just delivering outputs. And certainly not sustainable and inclusive impact.

To plan relevant activities and do useful monitoring, it needs to be clear which changes the programme is expected to achieve at outcome level. Shortsightedness at outcome-level is also easy to spot: such ToCs have fitted activities and outputs into the ToC space. The consequence is that there is literally no space to detail out the outcome level beyond one “column”. It is unclear which actors are expected to do what differently, to connect strategies with outputs, to impact. Based on our experience, we advise to collectively zoom into the result level which organisations and projects have influence over (not control) - where local actors are doing things differently. It is important to make the vague and woolly concrete and clear so the ToC is actionable and monitorable.

For example, “improved enabling environment” is a big and vague intended outcome. It might have different meanings for different stakeholders, it is unclear what needs to be done to make an “improved enabling environment” happen. By disaggregating “enabling environment” into for example “the Department of X has approved new policy Y”, “Department of X has a plan and budget to implement policy Y” and “Citizens in district B benefit from the implementation of policy Y”, the intended outcomes in the ToC become much more useful to plan activities for and monitor progress. Our advice is to zoom into collectively clarifying the detail of the otherwise missing middle of intended outcomes. We advise organisations who want to measure impact (the hot thing, still) but do not have a ToC yet, to first get clarity on the missing middle of outcomes, and decide what to monitor at that level. Because if they do not have clear via which outcomes the impact is expected to be achieved, even if they do measure positive impact, they will have a hard time convincingly connecting it to their own intervention.

5. Less data is much more

With mobile data collection tools, it has become so much easier to gather a lot of data, quickly. We’ve seen examples of organisations that have collected so much data that analysing, interpreting and using it for decision making has become infeasible. At Akvo, we believe that only data which will be used for learning, decision making and reporting should be collected, and then only if such data is not already available from secondary sources.

I have already explained the importance of first deciding what the intended results of an intervention are before planning activities and choosing indicators. If this process is followed, the risk of having a long list of indicators is much smaller. The point of departure should be “which intended results do we need to monitor to learn, steer and report? Which indicators do we need to monitor those intended results?” rather than “which indicators are interesting to collect data for?”. In the first approach, it will be clear how the collected data will be used, for what purpose, and by whom. In the second, there is a risk of collecting too much data and running out of resources, whilst the data is not used for anything apart from reporting because the indicator scores are disconnected from a change logic. The first approach supports the generation of actionable insights, the second one adds data to the data graveyard.

Collecting less data has another important advantage. It saves respondents of surveys a lot of valuable time. People who are expected to give away their data for free only benefit indirectly at best from the findings of the data collection. When less data is collected, organisations save resources for other important things, such as reflection and interpretation workshops with respondents and other stakeholders to make the best use out of the monitoring findings, at the level closest to where the changes happen. This way, monitoring data supports increased effectiveness of programmes.

6. Use it

A good ToC is one that is used. I have described how a ToC demystifies the missing middle of outcomes; how it generates a co-owned clarity on what needs to be achieved, and who (in a partnership) will do what to make that happen; and how it ensures useful monitoring, not just for reporting, but first of all for learning and steering.

With insights from reflecting and interpreting monitoring findings, a ToC helps to assess whether a programme is doing the right things, and whether they are doing the things right. If not, the ToC is flexible, improvements can be made to it, and importantly, adjustments can be made to the planning. That is why we advise to do the reflection and interpretation of monitoring findings in a collective sensemaking workshop, followed by a ToC review, right before the planning of the next year. So that all insights can be used straight away to inform strategic decisions, allocate resources, and adjust / enrich / improve / replace activities where needed. This sounds obvious, but you’ll be surprised how many organisations do their yearly monitoring just before annual reporting, where the opportunity to steer is minimal. When the first purposes of monitoring are learning and steering, it will be timed before planning.

7. Do not DIY

Hopefully this far into the blog you are convinced of the importance of designing a programme well, and that dedicating resources to developing a ToC saves and even generates money. Then one last piece of advice: invest in an experienced ToC facilitator, an outsider, who takes care of the process and the methodology, who ensures a productive flow, and knows when good is good enough. That way, the team of professionals will not get stuck in discussions, and everyone in the workshop can focus on the content. Hiring an experienced ToC facilitator is more efficient, it saves time, so it actually requires less investment than doing it in-house. A risk of doing it yourself is that it will take too long, the participants might feel it is leading nowhere and producing nothing concrete, and you will generate an allergy against ToCs, or even multi-stakeholder participatory processes.

Do you want to talk to one of our experts?